Caelum, nón animum mútant, quí tráns mare currunt.

— Quintus Horatius Flaccus, Epistulae

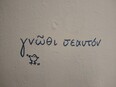

Ἀναχωρήσεις αὑτοῖς ζητοῦσιν ἀγροικίας καὶ αἰγιαλοὺς καὶ ὄρη, εἴωθας δὲ καὶ σὺ τὰ τοιαῦτα μάλιστα ποθεῖν. ὅλον δὲ τοῦτο ἰδιωτικώτατόν ἐστιν ἐξόν, ἧς ἂν ὥρας ἐθελήσῃς, ἰδιωτικώτατόν ἐστιν, ἐξόν, ἧς ἂν ὥρας ἐθελήσῃς, εἰς ἑαυτὸν ἀναχωρεῖν. οὐδαμοῦ γὰρ οὔτε ἡσυχιώτερον οὔτε ἀπραγμονέστερον ἄνθρωπος ἀναχωρεῖ ἢ εἰς τὴν ἑαυτοῦ ψυχήν, μάλισθ᾽ ὅστις ἔχει ἔνδον τοιαῦτα, εἰς ἃ ἐγκύψας ἐν πάσῃ εὐμαρείᾳ εὐθὺς γίνεται: τὴν δὲ εὐμάρειαν οὐδὲν ἄλλο λέγω ἢ εὐκοσμίαν.

— Marcus Aurelius, Τὰ εἰς ἑαυτόν