Perugia

Recently, I was recommended a trip to Perugia to attend the Umbria Jazz festival (my friends are pochi ma buoni) — or rather was compelled to go the moment I saw how incredible the program was, with artists such as Herbie Hancock, Marcus Miller, and Jacob Collier all in the same festival.

While it was challenging to balance working, exploring the city, and watching all the amazing concerts (and trying to get some sleep), I still managed to run around and see most of the places I had planned for my — tragically short — four-day stay. The result is this post, which is by far the longest I have written (and that is without even going into the festival itself, which will have to wait for another time), but that is just how amazing this place is.

people

Perugia, as many major Italian cities, is ancient. Its origins go back at least three millennia, a fusion of Umbrian, Etruscan, and Roman history. The modern center is located where the ancient Etruscan acropolis rose, about 300m from the valley of the Tevere, on top of two hills: Colle Landone and Colle del Sole, and is still delimited by two concentric defensive walls: one built by the Etruscans in the IV century B.C. and a second built after the expansion of the city in the mediaeval period.

Umbria is the region right at the center of continental Italy, and its capital Perugia is located roughly at equal distance from Firenze and Roma (150km) and Milano and Napoli (400km). In mediaeval times it was part of the “Byzantine corridor” which connected the Eastern Roman empire, centered in Constantinople (modern Istanbul) after the fall of Rome, to the regions it still held in central and southern Italy.

This central position made it a place of confluence of three important cultures of the ancient world:

-

the Umbrians, the original people of the region, who settled in the surrounding lands in the XI–X centuries B.C. and on the hill where Perugia was built in the VIII century,

-

the Etruscans (the inhabitants of Etruria, modern Toscana), who refounded the city with their Umbrian neighbors around the VI century, making it one of the largest of their territory, and eventually formed an (ultimately unsuccessful) alliance against…

-

the Romans, who incorporated both Etruscans and Umbrians in the III century into their ever-increasing empire, not only geographically and politically, but also adopting many of their cultural aspects — the Etruscan contribution to Roman culture is comparable to that of the Greeks.

In fact, the river Tiber, which flows from the southern end of Emilia-Romagna all the way to the port of Ostia in Rome, was for centuries the dividing line between the ancient regions of Etruria and Umbria, and Perugia sits right between them. Those who have been to Tuscany will certainly recognize a similar style.

The perfect place to learn about this is Museo Archeologico Nazionale dell'Umbria, in rione San Pietro on the south-east side of the center, right next to Basilica di San Domenico, which houses, among many other historical artifacts, one of the longest intact Etruscan inscriptions ever found, the III century Cippus Peruginus.

walls

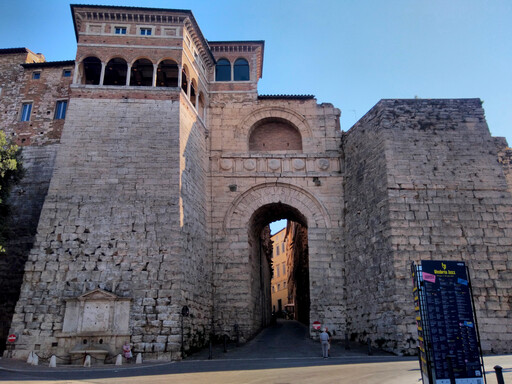

A striking features of the city are the walls that surround the historical center, with beautifully preserved monumental gates which provide passage in and out of it. The inner wall, with a circumference of about 3km, is less visible as parts of it were incorporated into other buildings over time. However, it contains the most distinctive of all the gates: Arco Etrusco.

Opening at the northern end of the old acropolis into the cardo maximus (the main north–south road of Roman cities, where today are located via Ulisse Rocchi, where I stayed, and corso Pietro Vannucci, the main street of the city center), its construction is in the same megalithic style seen in most Etruscan works, with large marble stones fit together by precise cutting, without the use of any binding. The arch bears the inscription “Augusta Perusia”, the name given by the emperor Augustus after his victory in the Perusine War (won only after a seven-month siege, a testament to the impenetrability of the city's defenses).

The outer wall, about 9km in length, is a clearer delimitation of the city center, and is where most of the gates can still be seen. Five of them give their name to the five rioni, the regions into which the old center is divided: Porta Sant'Angello, Porta Sole, Porta San Pietro, Porta Eburnea, and Porta Santa Susanna.

art

Beyond the classical period, Perugia was also a cultural center of the Renaissance, and many of the greatest works of the period can still be seen around the city, specially at the Galleria Nazionale dell'Umbria (which sadly I did not have time to visit).

Pietro Vannucci, one of the masters of the early Italian Renaissance movement, was born in what today is provincia di Perugia and spent much of his life in the city, resulting in his eponym, Perugino.

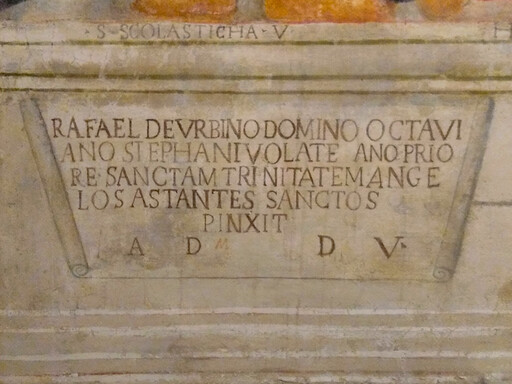

One of his pupils was Raffaello, regarded as one of the three greatest figures (along with Michelangelo and Da Vinci) of the High Renaissance period. Born in the Marche, he moved to Perugia in 1494, at 11 years old, to develop his craft under Perugino, and one of their collaborative works can still be seen here: the fresco Trinità e santi in Cappella San Severo, which displays the unmistakable style that can be seen in his later works, such as the Scuola di Atene in the Vatican.

around the city

Just walking around the historical center, admiring the architecture in Etruscan style, the wide views over the landscape of the valley, or simply the picturesque scenery of an old Italian town, is an attraction in itself. At every corner along the way there is something beautiful to stop and admire.

Venturing just north of the main square one finds a curious path which passes under via Cesare Battisti, down a large stairway, then over several streets on its way north-west. This is in fact an ancient aqueduct, an engineering marvel from the XIII century, which brought water from monte Pacciano, about 3–4km north, to the top of the Perugian hill, providing water for the city, including the famous Fontana Maggiore, through the use of pressure alone, without the aid of pumps. It later fell in disuse, but part of its course has been turned into via dell'Acquedotto, a scenic course connecting rione Porta Sant'Angelo to the city center.

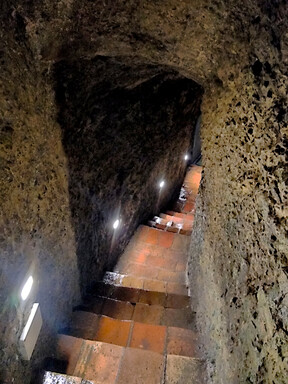

Not far from the fountain is a much older but equally amazing exemplar of aquatic engineering: Pozzo Etrusco. This is a well built in the III century B.C. by the Etruscans at the top of Colle del Sole. The underground of palazzo Sorbello has since been turned into a small museum, which can be visited along with the well itself. It is an amazing display of the engineering abilities of the Etruscans, penetrating 40m into the hill, with a capacity to hold almost 500,000 liters of water. The top structure, just below the street, is supported by two sets, each weighing nearly a tonne, of four limestone blocks, also here set in place without the use of mortar or other type of binding (there is a great depiction in the museum of how this engineering feat was accomplished).

churches

In the northern region, I visited what has become my favorite among all the churches I have been to (and those are a quite few): chiesa di San Michele Arcangelo. Because it is in fact a paleochristian temple from the V century (likely erected over even older Roman and Etruscan temples), it has an unusual style: its shape is round, and the presbytery is divided from the ambulatory by a circle of sixteen Roman marble columns in Corinthian style. Light enters the building primarily from twelve windows placed around the cupola, which sits just above the altar, rendering the interior even more austere.

If that were not enough, not only is the traditional mass in Latin still celebrated there, the temple sits on the so-called Line of Saint Michael, a series of temples dedicated to the archangel which form a straight line from Ireland to Israel, aligned with the last ray of sunlight of the summer solstice.

The cathedral, built in the XV century, stands right on the main square, next to Palazzo dei Priori and Fontana Maggiore, and contains many works of the Renaissance, as well as what tradition holds to be the Holy Ring, the wedding ring of the Virgin Mary and Saint Joseph.

A short distance south past the city walls is Basilica di San Pietro, which gives its name to both the region where it stands and the gate which leads to it. A stunning X century building, its 70m-high bell tower is the tallest construction in Perugia and one of its most distinctive. A favorite of mine, it also contains both a botanical garden and a reproduction of a mediaeval hortus conclusus, a symbolic monastic garden.

On the western end of the center is Oratorio di San Bernardino and Chiesa di San Francesco al Prato, the latter a XIII century church built in similar style to the church of Santa Chiara in the city of Assisi which, just 25km east, can be seen from many points in Colle del Sole.

ὅτι καὶ χαλεπώτερον δουλεύειν πάθεσιν ἢ τυράννοις· ἀδύνατον δ' εἶναι ἐλεύθερον τὸν ὑπὸ παθῶν κρατούμενον.

For the rule of the passions is harder than that of tyrants, since it is impossible for a man to be free who is governed by his passions.